Apologies for being away for some time, but life happens. One activity that took me off for a while was a trip to China. This was not a wine-centric tour, so I don’t have comprehensive notes about the Chinese wine experience, but I have a few observations that you might find interesting.

The Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin, as channelled by the Oxford Companion to Wine, reports that China is the seventh largest producer of wine on the planet. One might think, then, that the Chinese are great wine consumers, especially as very little of their wine is exported. However, when you factor in the enormous population, real consumption is only a fraction of a bottle per person per year. There is no tradition of grape wine consumption in China, although the history of rice wine consumption is very long, as indicated by the wine vessel shown below.

Bronze Chinese wine vessel from the Xia Dynasty (18th century BC). From the collection of the Shanghai Museum.

The new young middle-class urban generation has embraced grape wine to a certain extent, at home and in modern style restaurants within major cities. In such establishments it is possible to see a wine list, while in most Chinese restaurants grape wine is unknown, although beer is everywhere. You can also always order rice wine or, especially, distilled rice wine (báijiŭ) – both of these beverages commonly accompany meals. If you are able to obtain a list of a few available wines, most are red and almost all come from the large nationally distributed producers. In corner stores, you often can only find red wine. Remember, red is the colour of good fortune, while white is the colour of death. Since symbolism continues to be very important in China, you can understand why red wine (hóngjiŭ) predominates over white wine (báijiŭ). Notice that white wine doesn’t even get its own word (it’s the same as rice wine), while the word for red wine is often extended to mean wine in general.

Chinese wine production is dominated by a few large companies, notably China Great Wall Wine Co., Ltd. and the Dynasty Wine Ltd, as well as Changyu Pioneer Wine. Each has a wide range of wines priced from a couple of dollars per bottle up to fifty dollars or more. At the low end they are simple, fruity, and at least drinkable, while at the high end you get better balance and complexity. So far they have not fallen into the heavy overextracting overoaking trap, but are instead quite food friendly. Most of the better wines come from cooler climate regions in the north central part of the country, particularly Ningxia province, just south of Inner Mongolia.

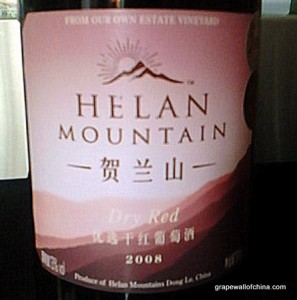

One of the best wines I encountered on my trip was from a smaller producer: Domaine Helan Mountain Cabernet. These lesser producers are harder to come across, but worth the effort. Several have recently won medals at the Decanter World Awards, including 2011 and 2012 International Trophy wins for He Lan Qing Xue Jia Bei Lan 2009 and Chateau Reifeng-Auzias Cabernet 2010, respectively, both in the Red Bordeaux Varietal under £10 category.

It is not yet possible to try Chinese wines at home (the LCBO only has a single example listed, and it is only available in a couple of Toronto stores). However, if the Chinese industry decides to make a concerted export effort, you can be certain that there will be a lot more “Made in China” wines in our future.