In the first half of this essay on wine myths, I focussed on eight misconceptions associated with buying wine. In this second half I shall be taking a look at ten myths about consuming and enjoying wine, including two that turn out to be generally correct and not myths at all. Again there will be two major subsections: Serving Wine, followed by Wine and Health.

Serving Wine

9. Red Wine with Red Meat, White Wine with White Meat

I know this myth has been fairly well demolished in recent years, especially since the landmark publication of the Rosegarten and Wesson book Red Wine with Fish. Still, I’d like to summarize my own thoughts, many of them distilled from the work of others before me, of course.

This maxim is mainly valid at the extremes. The traditional thick rare steak grilled on the barby calls for a young full-bodied red wine. The big fruit from the wine can stand up to the strong flavours of the grill while at the same time the (likely) pronounced tannins in the wine are muted by the meat’s protein. At the other extreme, a delicate poached white fish would be overwhelmed by anything but a fresh and crisp white. In between, however, the method of food preparation is more important than the base ingredient.

Take chicken as an example. With a delicate cream sauce, a crisp medium-bodied Chablis would go well, but pasta with a chicken (or any) tomato sauce cries out for a good Italian red. In fact, those wines are good with fowl in almost any form. Don’t be swayed by those half-hearted attempts to match light red wines with chicken or turkey – go with the gusto! Another example can be found with most Asian foods, where, no matter what the base ingredient, a white or rosé is your best bet. And, as always, experiment!

10. Serve Red Wine at Room Temperature

OK, so what’s room temperature? Well, the kernel of truth in this old saw is that when it originated, rooms, especially in winter, were pretty cold and draughty. So something like 16°C (60°F) was the norm in the house, and it was also a good serving temperature. But in our centrally heated homes wine is usually too warm at room temperature so it needs half an hour to an hour in the fridge before pouring. And err on the side of too cool rather than too warm because the wine will warm up fairly quickly in the glass in any case.

But what’s wrong with 21°C (70°F)? It’s really a matter of balance. At room temperature the harsher background flavours (alcohol and various bitter components) tend to be emphasized to the detriment of the overall experience. On the other hand, too cold and you lose a lot of the more delicate fruit and perfume notes while the wine will seem overly tannic. Since tannins are not an issue with whites and rosés. they can be served a little cooler (but not at refrigerator temperature) to bring out that lip-smacking freshness.

11. Open the Wine Early So it Can “Breathe”

There are two principal reasons why one might want wine to “breathe” a bit before you drink it. There may be some volatile (easily evaporated) components that are trapped within the wine or under the cork and that you would like to see disappear because they present some off flavours (“bottle stink”) The most common culprits are sulphur compounds (found more often under screw cap) or volatile acidity (otherwise known as vinegar). However, there is a much greater surface area and adjacent volume of air available to wine in a glass than in a bottle, so if those volatile components were able to escape during half an hour of sitting or “breathing” (and that’s unlikely), then they certainly should be able to do so within a minute or two after being poured.

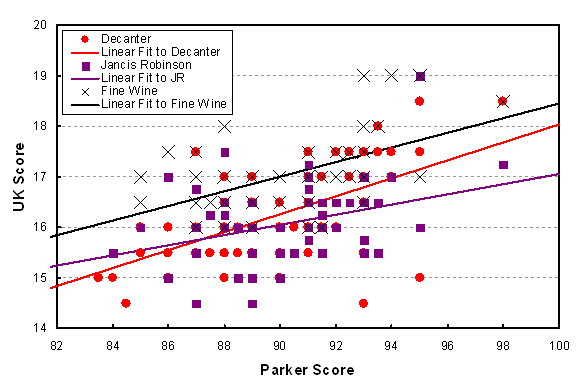

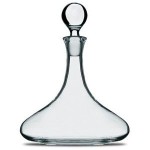

Decanter for young wines

The other reason is to expose a young wine to oxygen in the air. A little oxidation can soften the tannins and improve balance. However, the same argument applies here as in my previous point. If you really want to expose the wine to lots of air, then decant it into one of those wide base decanters (shown at right) and really splash it in, don’t pour carefully. Slow and gentle decanting is for old wines where you want to separate the wine from the accumulated sediment without exposing that liquid gold to much oxygen. And that thought provides a segué to the next myth.

12. Old Wine is Better

Like all of these myths, there is always a kernel of truth at the centre, but in this case it might be expressed as: Old Wine Can Occasionally Be Better. Most wines are not made for long aging, rather for “trunk aging” (or “boot aging” for some) on the way home from the wine shop. On the other hand, most wines will not be damaged by lying around for a year or two – some may even improve slightly. There is a small subset of wines that should generally be consumed within the first year after bottling, such as crisp light Vinho Verde or light rosés. At the other end of the spectrum is the small subset of wines that benefit from significant aging: Bordeaux, Burgundy (red and white), Barolo, Brunello di Montalcino, many Rieslings, and most of the better sweet wines, among others. But all of these wines do eventually subside into senility and finally, death. It may take 10 years, it may take 20 or more, but it happens to them all. Don’t wait for it.

In fact, for most of us, consuming wine when it is a little younger than peak perfection is usually preferable to a bit beyond its best by date. And it should be said that many people do not, in fact, enjoy the changes wrought by years in the cellar, when the fruit fades and the tertiary aromas are brought forth. The best way to find out for yourself is to buy a case of decent Bordeaux, for example, and then have a bottle every year or two in order to understand how it ages. Sure, that takes time, but you can drink younger wines in the meantime as well as having more than one case slumbering in the cellar.

13. Good “Legs” Mean Good Wine

How often have you heard someone with a small but dangerous amount of wine knowledge raise a glass to the light and comment on the fine “legs” or “tears” running down the side of the glass and how this must be a good wine. Contrary to this myth, however, the presence of legs is not a function of wine body or glycerol content or quality in general. It mostly means that the wine contains around 12% alcohol or more (but we already knew that, right?) and that the glass is clean, nothing more. Although the phenomenon is fun to watch.

Legs are a result of the Gibbs-Marangoni Effect. The wine will wet the sides of the glass, slowly on its own, or rapidly if assisted by swirling the wine in the glass. Then as the alcohol evaporates preferentially with respect to the water, the liquid beads up on the side of the glass and eventually runs back down under its own weight. The magnitude of the effect depends in part on the interfacial tension between the liquid and the glass, which explains why dish washing also makes a contribution.

Wine and Health

There is a lot of information on this subject in my earlier post; here I’ll focus on the myths and misinformation associated with wine and health, and I’ll end with two beliefs that are still controversial and may not be myths at all.

14. Wine is Bad for Your Health

Let’s tackle that main overriding myth right off the bat. Again, there is some truth at the centre of it. First, very high levels of alcohol, consumed frequently, are extremely bad for your health – I think everyone can agree on that. Second, moderate levels can be unhealthy for you or someone else when combined with the operation of a motor vehicle or heavy machinery – again, not much dispute there. Third, it has been well established in recent years that alcohol consumption contributes to the risk of developing cancer. The effect is negligible at low levels of consumption but does rise monotonically as consumption increases. There can be other negative effects at low to moderate levels, but cancer is the biggie.

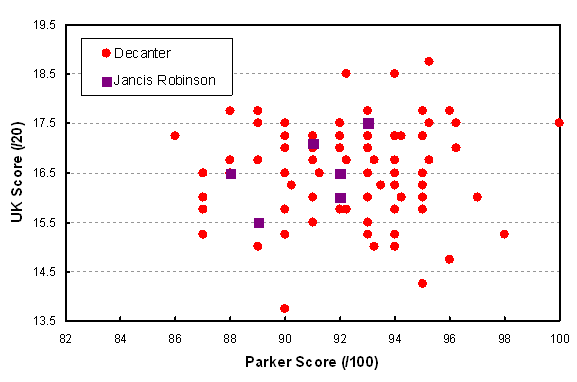

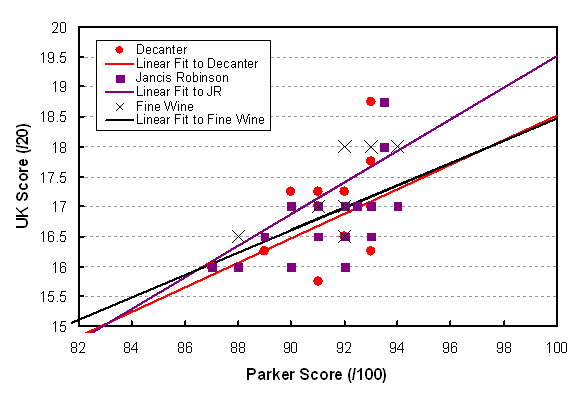

What’s missing here is the significant health benefits derived from consuming alcohol, particularly for the cardiovascular system, but in other areas as well. These benefits kick in quite quickly and are near maximum with only a very small dose (around half a glass of wine, for example). Meanwhile, the detrimental effects accumulate slowly with dose, so that for moderate consumption they are greatly outweighed by the benefits. The result is what’s called a “J curve” (a somewhat fanciful illusion to the shape of the curve), as shown in the graph below.

The relationship between alcohol consumption and risk of mortality (mathematically fitted to data). Risk is reduced for very low consumption and then rises, reaching the non-drinker (baseline) risk at ~2 drinks per day for women and ~3 drinks per day for men (a standard drink is considered to contain 14g of alcohol).

The recommended consumption level of 1 drink per day for women and 2 drinks per day for men results in a significant net health benefit (i.e. lower mortality risk). It takes at least 2 drinks per day for women and 3 for men before the risk returns to the same level as a teetotaller. This graph provides a simplified summary of the results of the meta-study by Castelnuovo et al. There is also some evidence that food consumption reduces the effects of alcohol. At least one study has shown that a meal eaten with alcohol not only resulted in a 35% reduction in peak blood alcohol content, but it also took 36-50% less time to metabolize the alcohol.

I think the extreme prohibitionist view, at least from the medical profession, comes from the Hippocratic requirement to “do no harm.” If a medical practitioner only looks at the deleterious effects of alcohol and not at the entire health of the individual, then that approach is understandable if not sensible. However, it is a disservice to the 90% of the population who are not alcoholics and who do not drive after having had too much to drink.

15. Sulphites Cause Headaches

Some people suffer from headaches after drinking wine, especially red wine, and often within minutes of consumption. These headaches are frequently blamed on the sulphites in wine, or on the tannins. However, it is now known that sulphites do not cause headaches and are not allergens (they are not proteins, for one thing), although they may cause a reaction for asthma sufferers (and this is the reason that sulphite content may be quoted on the label, not because of headaches). After all, there is a lot more sulphite in dried fruit (two ounces contain over 10 times as much as a glass of wine) and in prepared meats. In fact, the human body naturally produces around 1000 mg of sulphite per day, some 20 times greater than the contents of an entire bottle of wine.

Tannins too cannot be blamed for a wine headache, except perhaps in the case of the unfortunate few who suffer from migraines. So what is the source? Well, there is a lot of discussion about the cause, complicated by the fact that there are hundreds or even thousands of naturally occurring substances in a glass of wine. Some of the more likely culprits are naturally occurring histamines, prostaglandins, tyramine, or residues from the yeast or bacteria involved in fermentation. The bottom line, however, is that no one really knows what causes a wine headache (other than the one you experience in the morning after having imbibed far too much the night before!)

16. Wine, Especially Sweet Wine, is Full of Calories

Calories in wine arise from the alcohol and from any residual sugar. Therefore the caloric content of a glass of wine can vary. Each per cent of alcohol represents 10mL per litre, or 7.89g of alcohol, and alcohol contains 6.9 calories/g. Sugars (and carbohydrates in general) contain about 4.1 calories/g. Sugar in wine is usually measured in g/L. Therefore the caloric content of a 5oz (150mL) glass of wine is:

C = 0.15 x (A x 7.89 x 6.9 + S x 4.1)

Here A is the percentage alcohol by volume, S is the sugar content in g/L and C is the number of calories in a normal glass. For example, a completely dry wine of 14% alcohol contains 114 calories, whereas a sweet German wine with 8% alcohol and 4g/L of residual sugar contains 75 calories! So sweet doesn’t necessarily equate to high in calories. Fermentation simply converts one form of energy delivery into another. Note, however, that a glass of fortified wine like port, with 20% alcohol and 100g/L of sugar weighs in at over 400 calories. Fortunately, we tend to drink smaller glasses of fortified wines, so a 2oz glass is “only” 160 calories.

Now that we know what’s in a glass of wine, how does that compare with other drinks? Well, a 12oz glass of 5% beer contains around 150 calories, the same size of soda pop contains 132 calories, 6oz of orange juice contains 84, and milk has 102 calories in a cup (8oz). So what’s the verdict? Unless you’re drinking only water and diet drinks, everything has calories to a greater or lesser extent. As always, especially with alcohol, the message is quantity. Just don’t drink too much! Even that bastion of dieting, Weight Watchers®, has nothing against a glass of wine – it just goes into the calculation of total daily consumption. Be moderate and you’re fine. We do need calories (energy) to live – just don’t overdo it.

17. Pregnant Women Should Drink No Alcohol

Here’s one that may not be a myth at all. First, however, it needs to be made clear that the statement is trying to differentiate between light alcohol consumption and none at all. It is beyond dispute that heavy drinking is a serious issue and often results in Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Moderate alcohol consumption can result in less serious but still significant Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Therefore, the current recommendation of the health authorities of most western countries (e.g. U.S., U.K., Canada) is complete abstinence during pregnancy. But what about very light drinking (e.g. a half glass of wine once in a week)? Here is where the only controversy lies.

Two recent studies, one from Denmark and one from the U.K., both show a slight benefit to the child from light alcohol consumption by the pregnant mother. However, other studies show the opposite outcome, although the effects are always small. Most of the variations are likely due to other factors that may differ systematically between those who consume none and those who consume a little alcohol during pregnancy. These effects may work both ways, as described here and here.

Alcohol is a known teratogen that passes easily across the placental barrier. At the end of the day, it is that clinical knowledge that is the basis for a total ban on alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Now all potentially dangerous substances do have a safe level below which they are not harmful. But if that level is a trace amount only, then a total ban is sensible. The problem is that with the contradictory studies that are out there, we don’t really know what the safe level. Therefore the injunction against any drinking at all is reasonable. At the end of day, however, if you are pregnant and have a sip once in a while, especially with food (which slows metabolism of the alcohol), the likelihood of doing any real harm is remote – don’t fret about it.

18. Red Wine is the Healthiest Form of Alcohol

Here’s the other myth that contains more fact than fiction, but to a certain extent the jury is still out. The benefits of consuming wine in moderation are real, as I detailed in the first part of this double post, and in a previous post, Is Wine Good for You?. The question is: are the benefits greater from red wine than from other alcoholic beverages?

Those benefits arise from the alcohol itself (little controversy there), possibly from antioxidants (flavonoids and polyphenols such as resveratrol, for example), and maybe from other trace components. Ethanol (ethyl alcohol, i.e. beverage alcohol) is well known to increase (good) HDL cholesterol and reduce (bad) LDL cholesterol, thereby providing cardiovascular protection.

The effects of antioxidants are less clear and conflicting studies continue to be published. In general, however, the quantity of antioxidants required for clinical benefit is so great that the amount of alcohol consumed to obtain it would kill you! Resveratrol in particular is often cited for its benefits with respect to blood sugar control, cognition, cancer fighting, and weight maintenance. However, a recent study has determined that dietary resveratrol, including that in wine, does not provide any health benefits, probably because the dietary quantities are so low, as mentioned above. Now, popular press reports of this study have tended to sensationalize it by equating resveratrol with all of the benefits of drinking wine, which we know is not the case.

All right, alcohol in moderation is good in general. So what about the purported advantages of wine, and red wine in particular? One interesting study from Spain showed that red wine consumption decreases the incidence of the common cold by 40%, while there was a smaller reduction with beer or white wine and no effect for other forms of alcohol. There is other marginal evidence out there, but the bottom line is that red wine is at least as good as other wine and perhaps better for you, but the differences are small. This myth cannot be considered to be true or false, for now.