I find that there are two connotations of the word “private” when applied to the LCBO. First, there are the continuing calls for privatization of the LCBO’s business. In fact, it seems to be routine for every political party to call for privatization while in opposition. Right on cue, we have recently heard that familiar call from the Conservative party. However, as soon as a party takes over the government, the idea is always dropped. The closest we came to anything happening was in 2005 when the government of the day set up a blue ribbon commission to study and recommend the best future direction for the beverage alcohol business in the province. The unanimous recommendation of the panel was for full privatization, so naturally the report was put on ice and any further discussion was quashed. Since it was no longer up for public discussion, it effectively became “private” as well (the second connotation of the word). Fortunately, the report is still available for perusal on line. So, let’s take another look at the report and the panel’s recommendations in more detail and try to get a better idea of what the options might be.

There were four members of the Beverage Alcohol System Review Panel (BASRP), none of whom had any financial interest in the industry. The chairman was a former Vice-Chair of the LCBO, so its workings were well understood. The other members were a former Commissioner of the OPP, a corporate CFO, and a senior banking executive. Therefore the major concerns of social responsibility and revenue generation were also well represented. The terms of reference were to undertake a broad review of the beverage alcohol system and recommend how to get better value for consumers and government. Any recommendations had to maintain or enhance each of these five factors:

- Socially responsible storage, distribution, sale, and consumption;

- Convenience, variety, and pricing for the customer;

- Value to the taxpayer;

- Reuse and recycling;

- Promotion of Ontario products.

In order to fulfill their mandate, the panel members began by studying options from many other jurisdictions in Canada, U.S., U.K., Australia, and New Zealand, alongside an operational analysis of the present system in Ontario. Then they put this information together to identify a number of viable options for Ontario. Each of these options was subjected to analysis, both qualitative and quantitative, as well as risk analysis. Five options were identified as the most promising and one was unanimously selected as the final recommendation. The five options are described in the following table:

| Option | System | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Licensing | Retailers and wholesalers are licensed by public sale for five year periods, and pay an annual fee; Limit the number of retail outlets; Set a minimum price level. |

| 2 | Retain/Improve | Status quo with improvements recommended by an operations review |

| 3 | Divestment | Sell LCBO assets to a non-profit beverage alcohol authority (monopoly) or through a public offering |

| 4 | Joint Venture | LCBO, BRI, and winery stores merge into a single organization |

| 5 | Competition | Private retailers and wholesalers are licensed while the LCBO, BRI and winery stores remain in business in direct competition |

Now I’d like to look at the advantages and disadvantages of each of these systems, especially in terms of the five factors (listed above) that need to be maintained or enhanced. I’m going to skip a discussion of social responsibility and recycling since both of these can be handled by legislation and enforcement policies that are essentially independent of the distribution and sales model. The focus is really on value to the customer and value to the taxpayer, with a nod to access to Ontario products. A summary is provided in the next table, following which I’ll elaborate on some of the most interesting or controversial points (Note: in this table the advantages are in bold while the disadvantages are in italic).

| System Option | Value to the Customer | Value to the Taxpayer | Access to Ontario Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 - Licensing | Improved price and selection through competition; Limits on number of retail outlets may limit specialty retailers; Minimum pricing policy may limit consumer advantage. | Increased revenue (est'd. $200M/year); Removes operational and investment risks from having government in the retail business. | Improved access to the system for small producers. |

| 2 - Retain & Improve | No improvement and prices may even rise. | Politically easy - no disruption; Potential for increased revenue through reduced costs and increased prices; Government remains in retail with associated risks and investment requirements. | No improvement. |

| 3 - Divestment | No improvement in competitive landscape, pricing or convenience. | Big chunk of change for the government; But, payment is one-time only; Government remains in retail with associated risks and investment requirements. | Uncertain pricing and access for small producers. |

| 4 - Joint Venture | No improvement in pricing or convenience; Competition landscape even worse that at present. | Rationalization of store locations and product offerings, providing operational efficiency; Government remains in retail with associated risks and investment requirements. | No improvement. |

| 5 - Competition | Increased competition; Improved pricing, selection, and access. | Increased government revenue; Complete restructuring not required. Profitability of LCBO uncertain as competitors would have much lower operating costs and LCBO cannot easily transform its very high cost structure; Government remains in retail with associated risks and investment requirements. | Improved access to the system for small producers. |

The only two options that are advantageous to the consumer are 1-Licensing and 5-Competition (which includes licensing but does not eliminate the LCBO). I have always been a proponent of the Competition option because it seemed to provide the best of everything. Perhaps that was at least in part because I was tired of hearing the LCBO constantly telling us how good they are. If they are so superior, then there should be no problem permitting competition because the LCBO would just grind their competitors into the ground! Now, however, I have been set straight by the BASRP. They assert that the LCBO cost structure is so heavy, with gold-plated stores and unionized staff being paid top dollar for stocking shelves, that they would fold under the pressures of real competition. This drives home the point that the government should not be in the retail business in the first place.

The recommended option is Licensing. In this scenario, the government sells off the LCBO’s physical assets and then auctions licences to private concerns for the right to retail or to wholesale beverage alcohol. Because the licences would expire after five years and bidding would again take place, and because there would also be annual fees, the panel estimated that the LCBO would net $200 million more than they currently make. That was in 2005 so the figure would likely be higher now. The two most important requirements, consumer value and taxpayer value, are both satisfied. Now, in order to deal with the other requirements,especially social responsibility, the panel does suggest imposing some restrictions.

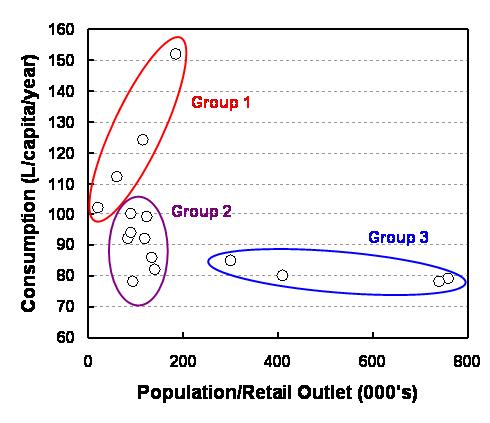

First, they propose an upper limit on the number of retailers allowed, both within a region and within the province as a whole. This idea is intended to allay concerns over social responsibility, as they claim that fewer retail outlets reduce consumption. However, their own data does not appear to support that claim. The following graph plots consumption/person/year versus population per retail outlet for many of the external jurisdictions that were studied. If the claim were true, then the data should show a clear drop moving from left to right. In fact, the data fall into three groups.

Dependency of alcohol consumption on number of retail outlets. Greater population/outlet means fewer outlets (right end of axis). The data fit into three general groups but there is no overall trend.

The data fall into three main groups. Group 1 (Iowa and Quebec at the bottom, UK and Australia at the top) shows the opposite trend to what might be expected – this trend likely has more to do with cultural differences than with access to supply. The bulk of the jurisdictions (several US states plus New Zealand) fall into Group 2 where there is no discernible correlation. Finally, Group 3 (all of which are Canadian provinces) shows relatively low consumption rates but almost no dependence on accessibility. In fact, government controlled Ontario, at 760,000 people per access point, had the same consumption rate as the fully private system in New York state, at 95,000 per access point. Once again, the position of Group 3 on the graph is likely a result of culture (since they are all the same country) rather than any direct correlation. All in all, there does not appear to be a strong reason for limiting the number of retail outlets. But, if that helps with making a change in the system politically palatable, then OK. It’s something that can easily be fine tuned at a later date.

The other important restriction is to set a price floor. This is trickier. Like it or not, it is perfectly reasonable for a licensing body to restrict the number of licences. However, price control of private industry is another matter entirely. Now, if there is a flat minimum price in order to prevent a lot of “two-buck Chucks” from appearing, then the situation is not too bad because that is the market space where cheap booze could be an issue. But if it is the markup that is regulated, then it’s a different problem. Then there is little chance for price competition, case discounts, and sale prices, even for premium products where mass market over-consumption is much less of a concern. Value to the consumer is significantly impaired.

Still, even with these flaws, the recommendations of the BASRP would be a huge improvement over the current situation. Let’s put these proposals back on the table. Let your MPP know what you think, for example through MyWineShop.ca. Turn this private affair into a public discussion.